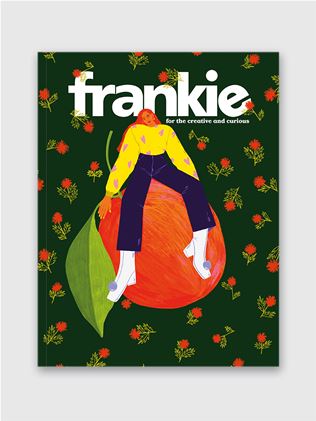

look what we made – artist nadia hernandez

“I think at first when people see my work it’s like, ‘Wow, it’s so positive, it’s so colourful.’ But then you spend more time with it and it might be quite confronting."

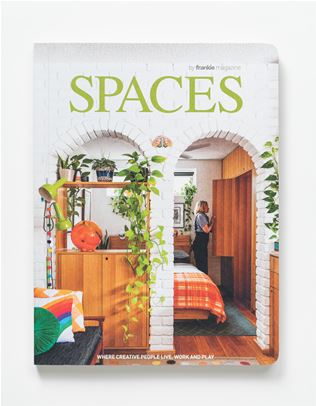

You might have heard of a little coffee table book by the name of Look What We Made. It's a compilation of inspiring chats we had with local makers of all sorts, including the chinwag you're about to read. If it tickles your fancy, you can pick up a copy over at the frankie shop.

Nadia Hernández interrogates her memories of Venezuela as if she’s being tested by a zealous examiner, trying to recall everything in meticulous detail. She’s scared she’s going to forget. She remembers the rocky peaks that surround her home, that eventually wind into the Andes; she would hike with her grandfather as he, a professor and plant physiologist, yelled out the scientific names of the notable flora they passed.

She notes that composer Simón Díaz was playing on the radio when her mother drove away from their home in Mérida, through cities and towns, until they got to the sea. There were birthday parties in the mountains and Sunday lunches with her family. The texture of the tiles underfoot in her grandparents’ bathroom and the deep wrinkles on their hands. “I’ve tried so hard to retain these memories,” Nadia says. “I’ve made a real conscious effort because since I left, things have changed so radically.”

It’s unsurprising that the multi-disciplinary artist finds it easiest to recall these sensory details – the touch and sound of her home. Nadia left Venezuela with her mother in 1999, the same year that Hugo Chavez won the presidency and introduced sweeping reforms that dramatically altered the country. After moving to Arizona while Nadia’s mum got her PhD, they settled in Queensland when she got a job at a university there.

Now in Sydney, Nadia works as a full-time artist, her energetic pieces appearing everywhere from indie galleries to massive public installations and even sleepwear labels. She has made stage costumes for the band Client Liaison and painted a life-size baby elephant sculpture for Golden Age cinema. Opportunities she can’t conceive would have happened if she’d stayed in Mérida – and to be honest, she sometimes has trouble believing them even now.

“If I had gone back home, I definitely don’t think I would have been able to become an artist, or have known that that was a possibility,” Nadia says. “It’s sad. I miss the place that I’m from, but I’m glad that I get to do what I love – and to discover what that even is.” Nadia and her mother had always intended to go back to Venezuela, but the rapid changes that were occurring there – or in Nadia’s words, the “scary authoritarian rhetoric” – prevented them from doing so.

This distance from both her home and her mother, who still lives in Queensland, ended up informing her practice. “I was missing my mum – we’d always lived together and speak Spanish at home. It’s like our relationship was what enforced my identity as a Venezuelan person,” she says. “When I moved to Sydney I felt something was missing, and that I had to retain that thing.” Nadia began experimenting with paper cutouts, creating art for and about people back in Venezuela as a way to feel connected.

Her pieces – which are sometimes paper collages, increasingly oil paintings and occasionally sculptures, sketches and murals – are tethered to Venezuela in a couple of different ways. In one respect they function as vehicles of preservation, recording aspects of the country’s folk art and popular tradition.

While studying fashion, Nadia returned to Venezuela to work with an artisan weaver who taught her his craft, and inspired her to create art specific to her birthplace. “That was the start of it – of my culture coming into my work,” she says. Nadia uses her distance from Venezuela as the catalyst to delve into her own memory, leading her to look inside. As things become “politically worse” in Venezuela, she uses art as a way to retain hope and encourage her family back home. “That’s when the political slogans started creeping in,” she says, laughing.

There’s a deceptive simplicity to Nadia’s stuff: it’s colourful and full of vibrant shapes and welcoming cartoon faces. Then you look closer, and one of those ‘fun’ disjointed characters is holding a gun. And the gun is pointed at someone in a wheelchair. “And the ones who didn’t die were incarcerated,” yells colourful Spanish text over the scene. Nadia’s work is frank but it isn’t without hope – she’ll often include slogans like “PAZ!” (PEACE!) asserted in frame.

This tension between despair and joy is a stylistic reference to Latin American folk art, using the sense of colour, movement and energy to draw people in. “I think at first when people see my work it’s like, ‘Wow, it’s so positive, it’s so colourful.’ But then you spend more time with it and it might be quite confronting,” she says.

In this context, anguish and hope are

connected, with a recognition of turmoil

and disappointment sitting side-by-side with optimism. When thinking about her strongest childhood memories from Mérida, Nadia explains a New Year’s tradition where you create an effigy of firecrackers to represent

the old year – it could be dressed as a specific corrupt politician – and the figure is burned at the end of the night to symbolise hope for better times ahead: “It’s kind of meant to be about forgetting all the bad things that have happened in that year and starting fresh. I always remember all of those traditions.”

Even though her work is anchored to Venezuela, Nadia reckons it’s fascinating to see it resonate with Australians in a completely different context. When planning a recent mural in Toowoomba, Queensland, Nadia decided at the last minute not to translate her slogans into English, as political protests back in Venezuela weighed heavily on her mind. “I was just like, ‘I need to say something about this. But... you’re in Toowoomba!’” she says, laughing. “How are people going to take this?”

So Nadia painted the mural using the Spanish word for freedom, “LIBERTAD!”, and used the colours of the Venezuelan flag. While she was painting, three local women visited her and asked what the slogan meant. “I told them

and they said, ‘Oh my god, that building used to be a club and we used to come and dance topless! We experienced so much freedom in that building!’"

"It was really cool, because I was so worried about how this work was going to relate to this town. For me it’s ultimately about people seeing themselves in the issue. Thinking about political turmoil that’s happening in other countries can be quite depressing, but to have this angle, for people to relate to it and have that conversation? That’s the ultimate goal.”

Keen for more artistic inspo? There's pages and pages of it in Look What We Made, which you pick up over at the frankie shop.

_(11)_(1).png&q=80&h=682&w=863&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)