women who fought the power

Meet some of history’s most tenacious ladies, who weren’t afraid to tell The Man where he could stick it.

Meet some of history’s most tenacious ladies, who weren’t afraid to tell The Man where he could stick it.

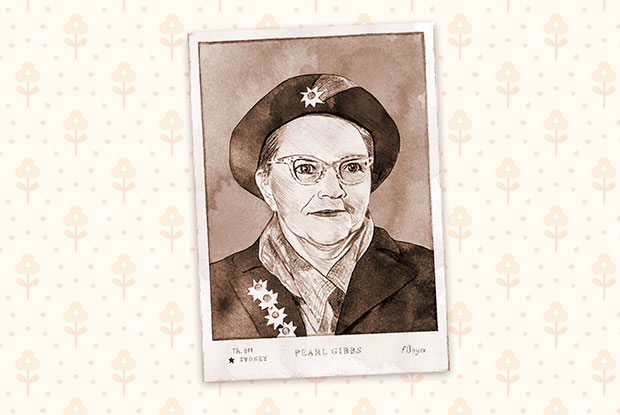

PEARL GIBBS

INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN ACTIVIST

1901-1983

On the scale of horrific, fucked up shit, the treatment of Australia’s First Nations people is right up there. Colonisers massacred them, raped them. As recently as 1902, a Tasmanian member of parliament argued that there was no need to include Indigenous people in the national census because, in his words, “There is no scientific evidence that an Indigenous Australian is a human being at all.” These days, of course, we all know that’s racist bullshit – and folks like Pearl Gibbs are largely to thank.

Pearl, born in 1901, faced discrimination from birth. Her local state school in Cowra, New South Wales, told her she wasn’t welcome (“Sorry, no blacks,” was the rationale). At 16, she went to Sydney to work as a cook, where she met other Indigenous girls who’d been taken away from their families to do household duties for white people for basically no money – and get treated like crap in the process. Pearl’s response? Report the injustices to the state-run Aborigines Protection Board, which, at the time, controlled everything Indigenous Australians did, including where they lived, who they married, where their kids were brought up – you name it. Oh, and there were no Indigenous Australians on this board, of course – until people like Pearl petitioned to get on it. (In fact, she was the first woman on one of these ‘welfare boards’, too.)

She campaigned her entire life for Indigenous rights, sending clear and far-reaching messages thanks to her speech-making prowess. Pearl even became the first Indigenous woman to speak on Australian radio airwaves, a platform she used to bring home white people’s cruelty and injustice against her people. “Our girls and boys are exploited ruthlessly,” she declared. “Please remember, we don’t want your pity, but practical help.”

Then there were the huge demonstrations she helped organise, like the Aboriginal Day of Mourning in 1938, and a certain rally of around 500 Indigenous folks at the Sydney Town Hall. The latter launched a national petition to change the parts of the Australian Constitution that discriminated against Indigenous people, which in turn led to the Referendum of 1967, asking the public whether Indigenous Australians should be counted in the census. Ninety per cent of Australians voted ‘yes’.

Pearl remained politically active as long as she physically could. In 1981, two years before her death, she spoke passionately in an interview about the hiring of young Aboriginal girls: “They wholly and solely belong to whoever employed them – and I call that slavery!”

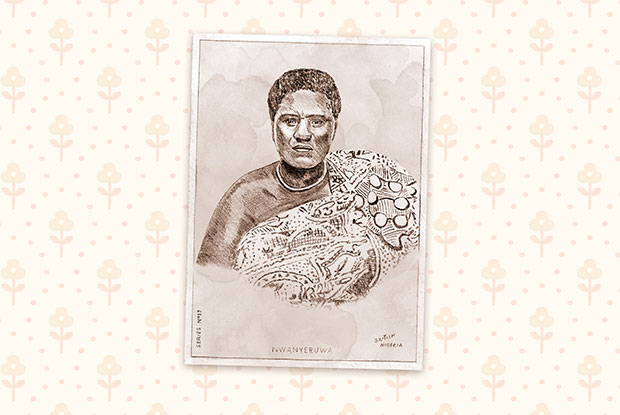

NWANYERUWA

IGBO WOMAN

Here’s something you probably already know: British colonists were extreme arseholes. They claimed whole chunks of Africa for themselves, including Nigeria, and when the Depression hit them hard in 1929, they went, “Hey, why don’t we just tax more from the people who live on the land that we don’t actually own?” Not a direct quote, but nevertheless, an accurate depiction of the sentiment. The plan was supposed to go like this: 1) warrant chiefs – i.e. local men the British had appointed to do their bidding – would send tax collectors to extract money from the only people who weren’t getting taxed at that point, the women; 2) the women would hand over money (which they didn’t have, but, you know, small details); 3) the British would have more money to spend on pie.

There were a few problems with that plan. And specifically, one big one: an elderly woman called Nwanyeruwa. When the tax collector came to her house and demanded she count the wives and livestock in her family, she asked him, “Was your mother counted?” He grabbed her throat, she grabbed his, and her cries brought one of her husband’s other wives to her aid. The dude left, but Nwanyeruwa remained pissed off. She complained about her treatment to the local warrant chief, Okugo, who didn’t care – he even suggested she was asking for it. Bad move. Because Nwanyeruwa had connections: other women.

Together, they were a mighty – yet peaceful – force. They rallied together to ‘sit on him’, the local Igbo ladies’ way of challenging male authority. ‘Sitting on a man’ involved all the women hanging out in front of the man’s compound, wearing their wartime outfits, bearing their breasts, and making up songs that detailed exactly what he’d done that was so fucked up – basically, a political sing-along. But Okugo couldn’t hack it. To the extent that he went after them with spears and arrows. Eventually, he burned his house to the ground and blamed them – but by that stage, the whole thing was bigger than just getting a point across to one warrant chief. Nwanyeruwa had started a movement.

Rapidly spreading across Nigeria, it became known as the Igbo Women’s War, with tens of thousands of women joining forces in the name of representation and equality. They marched, sang, occasionally looted, but were never violent – unlike the Brits. Finally, weeks later, the British stood down, withdrew taxation on women, and limited the warrant chiefs’ powers. The record doesn’t show what happened to Nwanyeruwa.

EDITH MARGARET GARRUD

MARTIAL ARTS INSTRUCTOR, SUFFRAGETTE

1872-1971

When you think of early 20th-century British suffragettes, you probably think of tea-sipping dames like Mary Poppins, who sang their way into our hearts and, eventually, through delicate negotiation, secured white women the right to vote. That image is bullshit, however, and the truth far more gripping. The fight for women’s rights was at times quite literal. Police used truncheons to bash ladies at rallies (some male ‘vigilantes’ also joined in), and at least three women died as a consequence. Others were held in prison and went on hunger strikes, so police rammed tubes down their throats to force-feed them.

It’s fortunate, then, that Edith Garrud, professional arse-kicker, was born. This relatively small woman (measuring roughly 149 centimetres) took an interest in martial arts at a young age, then travelled from her home in Wales to study in London with the first jiu-jitsu master to teach outside of Japan. By 35, Edith was a human hurricane – she even choreographed and starred in the first martial arts film made in the UK, Jiu-jitsu Downs the Footpads, in which she overcomes a pair of ruffians. But Edith had bigger targets in mind than fictional fuckwits. By this stage it was 1908, and suffragettes were getting beaten in the street – there were real-life fuckwits to take down.

She spread word about the benefits of ladies learning jiu-jitsu in the Women’s Social and Political Union’s newspaper. “The leverage lies in twisting wrists, elbows or knees; joints the way they are not meant to go,” she wrote. “In this art all are equal, little or big, heavy or light, strong or weak; it is science and agility that win the victory.” The WSPU embraced Edith’s tactics. She instructed suffragettes in hand-to-hand combat (aka ‘suffrajitsu’) and her signature move – flipping a cop over one’s shoulder and throwing him to the ground – at her secret dojo. She also trained them to use Indian exercise clubs, shaped like bowling pins, which could easily be concealed under their skirts; formed the ‘Bodyguard’, an elite squad of around 30 women who protected leaders like Emmeline Pankhurst from arrest; and provided alibis for fellow suffragettes, claiming they’d been training when they had, in fact, been out and about blowing up mailboxes.

Even though the suffragette movement was suspended with the outbreak of World War I, Edith continued to teach women self-defence. She is believed to have been the first female martial arts teacher in the Western world.

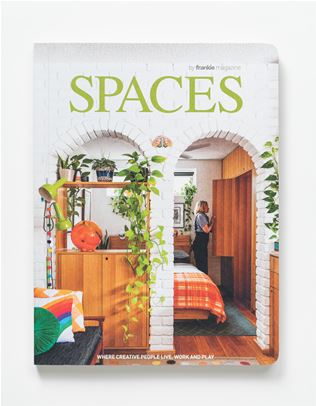

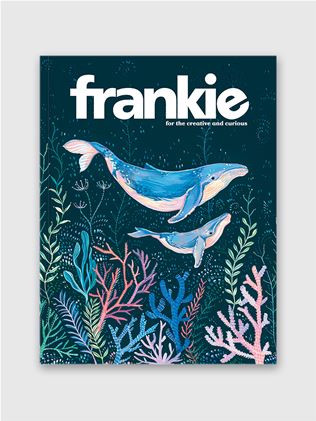

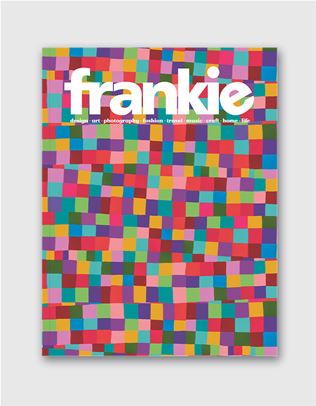

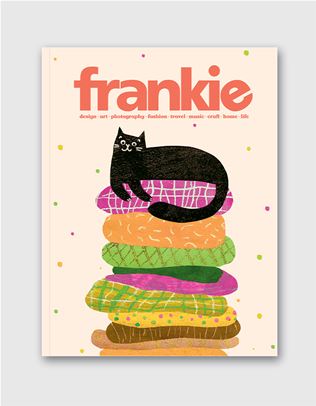

Learn about more history's pioneering ladies by picking up a copy of frankie 89, on sale now. Nab a copy here, or subscribe from $10.50.

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)