how tunes lift mental health, according to a music therapist

Elly Scrine uses music to mess with our minds (in a very good way).

There’s something that happens when a talented DJ hits the decks. They feel out the mood of the crowd, think about where they want to lift the room, then slowly, through the music they play, build and build until everyone there is on the same page: on their way to reaching a euphoric fever pitch. The fact that music and mood are linked is something we perhaps just intuitively know – but it’s a connection Dr Elly Scrine has dedicated their life to through their work as a music therapist, researcher and musician.

“We use music all the time to regulate our emotions,” Elly says. “I think we have an understanding of how powerful music is because we feel it through the course of our whole lives. We see how parents use music to bond or regulate their baby's emotional state. As children, we learn through music: we learn the alphabet through song. And in adolescence, music is everything. It’s how we form and develop our individual and social identities. It’s how we manage our moods.”

Music therapy, Elly explains, is about meeting people where they’re at – using music to achieve a non-musical goal. The applications are broad: music therapists work with all ages and abilities to treat a range of physical and mental conditions. Tunes can help non-verbal folks improve communication, children develop or refine their motor skills, or infants blossom in neonatal intensive care, and can also improve memory and attention, and even the body’s ability to deal with pain. It’s a common feature in hospitals, schools, aged care homes and prisons, among other settings. Elly’s focus is on mental health – in particular, working with young people.

“I think I would be happy to work as a music therapist in any context, to be honest,” they say. “But working with adolescents and young people feels really right to me, because adolescence is such an intense time for your emotions and mental health, as well as your relationship with music. You’re getting to meet these people when they’re forming their adult identities and initiating their life paths.”

The impact of music on the brain can be measured in chemistry and pictures. “We know that music activates the pleasure centres,” Elly explains. It releases mood-enhancing chemicals like dopamine and endorphins and lowers stress hormones like cortisol – but that doesn’t mean it can be applied in a one-size-fits-all manner. The same song may lift one person up while dragging another down. The opportunity to turn their life experiences into lyrics, to put their feelings to song, may be catharsis for one person while leaving another cold. Much like our brain chemistry, our relationship with music is deeply individual. “Your response to music is really going to depend on your mental state, your emotional and physical state, as well as your life experiences, or your cultural or social context,” Elly says. “In music therapy, we wouldn’t just be like, ‘Oh, you’re sad. Let me put on my favourite happy song.’ You have to understand the person, their needs and their own relationship to music.”

For example: “Often parents might worry that their teenager is listening to music that seems negative or antisocial – but that type of music might be relaxing for them. So, what looks negative might actually be a really healthy way of processing difficult feelings.” In their work, Elly points to the different ways music can be used to get to know clients and help them. One thing it offers is a way to open up honest discussions: rather than asking someone who’s perhaps withdrawn or anxious to put into words exactly what’s going on with them, they might be asked what music they’re most drawn to at the time. “It’s a way of approaching those difficult conversations in a less confronting manner,” Elly says, “and in a way that can open up a therapeutic relationship.”

A music therapy session could include anything from listening to music (sometimes even played live by the therapist) to writing lyrics and songs and actually singing or making melodies with an instrument. Elly has spent a lot of time working with adolescents in a group setting, where the focus is on songwriting and performance. Beyond offering a new way of expressing themselves, the communal environment also encourages those taking part to build connections with each other. “It’s more of a resource for them than, say, individual therapy, because they’re building community that can exist and keep existing outside of any kind of institutional space.”

The impact of music on individuals and society at large is far- reaching. It doesn’t matter whether you’re performing, writing lyrics or listening to songs. It also doesn’t really matter what kind of music it is; whether it’s upbeat or mellow, has lyrics or is purely instrumental. What matters is the specific relationship you have with what you’re making or listening to, and the impact it has on your own mood or mindset. Understanding this in yourself can go a long way, because the way we use music to temper or complement our mood isn’t always healthy. Playing a song that brings out darker, sadder memories can help us work through things – but the line we walk is narrow.

“Listening to a song you know makes you feel good has benefits for your mood, but you have to choose to put that song on,” Elly explains. “And alternatively, playing a song that makes you feel worse, or causes you to internalise or get stuck in the really hard stuff – that’s called rumination.” Dissecting music is Elly’s job in more ways than one. On top of their work as a music therapist and researcher, they also make up one third of electronic act Huntly. “We refer to it as ‘doof you can cry to’,” they reflect with a laugh. “Essentially, I think of it as dance music that allows for emotional catharsis.”

Though they describe therapy as their day job and being a musician as their night job, “it’s quite beautiful to look across my life and see music as the thread that ties all my projects together,” Elly says. “I use writing music as a way to process my own heavy feelings. Sometimes that means the songs are more upbeat or dance-focused, while others are slower.”

While Elly’s parallel careers are linked and, together, offer insight into the impact of music on the mind, the two are also distinct. “My music is my art, so it’s more for my own personal growth and identity work,” Elly says. “And, you know, hearing that people listen to or get something out of it is such a thrill. But my work as a music therapist is super-different, because it’s not about me – it’s about using music to support a client’s health and wellbeing.”

There are two key messages that come through most clearly while talking to Elly. The first is that music and mood, music and mental health, are undeniably linked. The second is that it’s vital to understand that the connection is deeply individual. “We feel music move us to tears at a concert or connect us to a person or a pivotal moment in our lives,” Elly says. “Through music, we can be with others and express ourselves and forge our identities – and as a result, we can feel connected to others, which is crucial for our mental health.”

Elly has put together a playlist designed to lift your mood – and, perhaps surprisingly, it isn’t all toe-tapping, hip-shaking bangers. They’ve applied what’s called the ‘iso principle’, which is used in music therapy for mood management. “If I was feeling a bit flat or down, just putting on a really happy, optimistic song might not work,” Elly says. “It’s about acknowledging where you’re at, meeting that emotional state, then using a playlist to gradually shift it.”

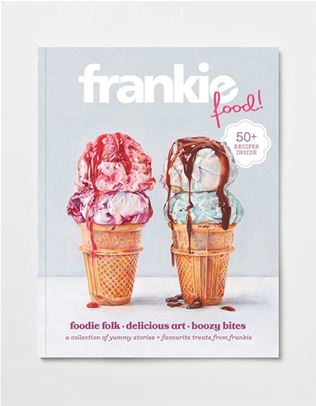

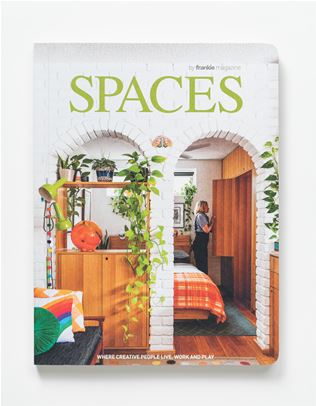

This story comes straight from the pages of frankie feel-good. Nab yourself a copy from our online store. Or, if you’re one of our New Zealand pals, grab the mag from your local Countdown supermarket or favourite bookstore.

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)