the life of maud lewis

Canadian folk painter Maud Lewis is the subject of a touching new movie, Maudie. She also had one heck of a life, mostly confined to a tiny one-bedroom house.

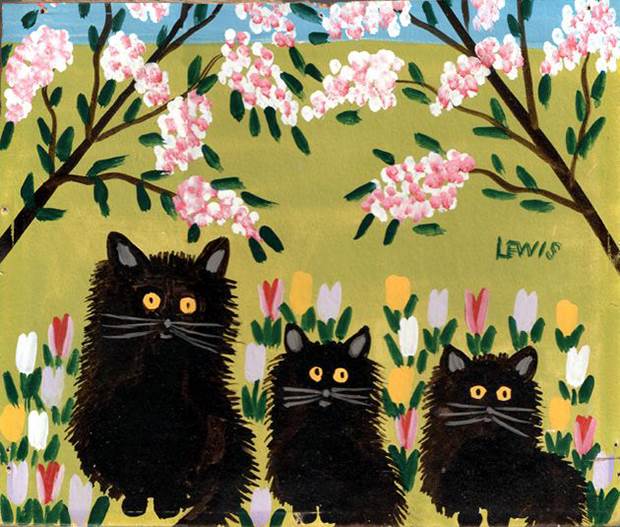

In a tiny one-bedroom house in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia, a lone woman sits with a palette and paintbrush. She gently applies paint to the walls, already covered with images she has lovingly created: bluebirds, daffodils, cats, cows, butterflies. They are bright and colourful, splashes of country life captured in brushstrokes. The artwork adorns the windows of the house, as well as household objects – the stove, the bread box, serving trays – and the wooden panels outside. A rickety old staircase sings in warm yellow.

This was the life of Maud Lewis – the Canadian folk artist at the centre of the new biopic, Maudie – whose cheerful, childlike paintings belied her difficult history. She spent 32 years living in the 3.5 square metre house with her husband, painting these charismatic pictures and selling them for no more than $10 a pop. Today, Maud’s paintings are worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Sally Hawkins stars in Maudie; Ethan Hawke plays Maud’s husband, Everett.

Born in 1903, Maud was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at a young age, limiting her physical ability – her shoulders were hunched, hands gnarled. She was teased at school and dropped out as a teenager, staying home with her mother, who introduced her to art. Maud began to make and sell Christmas cards for 25 cents each.

By her mid-thirties, Maud was an orphan, and her brother inherited the family home. She moved 100km north to live with her aunt, and it was there that she responded to an ad for a housekeeper, although her disabilities made it difficult to work.

The ad was placed by a fish-peddler named Everett Lewis, and a few weeks later, Maud and Everett were married. They moved into the small house – one without electricity or indoor plumbing – where they spent the rest of their days together.

Maud would accompany Everett on his daily rounds, selling her Christmas cards. They proved so popular that Everett started taking care of housework while Maud painted more prolifically – first on beaverboards and then on every surface of their home, which became her most magnificent canvas.

The Lewis house, painted by Maud.

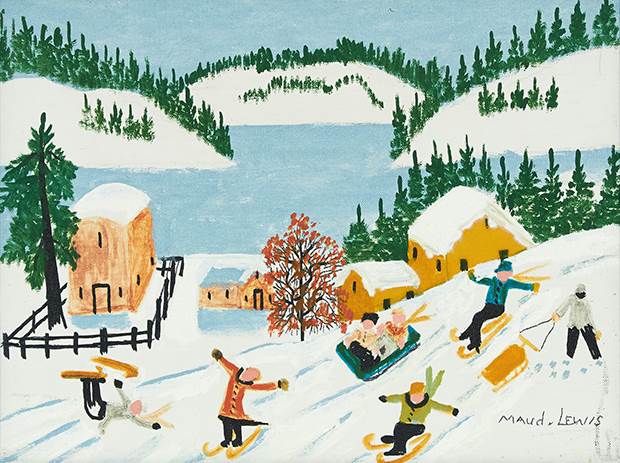

Skiing and Sledding Scene by Maud Lewis.

Her technique was simple – she used the paints straight, never mixing or blending colours. Maud’s joyful artworks depict her childhood memories and longings, imagined from inside the ramshackle house where she brought them to life. With no formal training, and having never seen another artist’s work, she just painted what she knew and felt.

But behind these sunny scenes was a relationship that was often fraught. Though Everett supported Maud’s art, gifting her with her first set of oils, he was also reclusive, gruff and, by many accounts, physically abusive. Living in such a confined space under these circumstances couldn’t have been easy for her.

Life was made even more difficult when Maud lost all mobility in her painting hand by 1964, and had to use her left hand as a motor. The artwork may look simplistic, but it was excruciatingly painful to produce.

Three Black Cats by Maud Lewis.

For most of her career, Maud was relatively unknown, but passers-by soon became enamoured with the funny little house, and stopped in to buy her paintings for a few dollars. In the 1960s, she was featured in Toronto’s Star Weekly newspaper, which boosted her profile – but her health was declining, and she was unable to complete many of the commissions that resulted from her newfound fame.

In the final year of her life, Maud split her time between painting and going to and from the hospital. She died in 1970 of pneumonia, and was buried in a child’s coffin.

After Everett’s death in 1979, the house began to deteriorate, but was saved by a group of passionate citizens, and in 1984 was sold to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. It was restored, and is today exhibited permanently as a part of the gallery.

Maud Lewis remains one of Canada’s most revered and influential folk artists – after her death, two of her paintings were purchased by then-US President Richard Nixon. Her artwork provides a peek into the busy, creative mind of a woman confined to a tiny room, and a humble, often hard life.

As she herself said in a 1965 interview, “As long as I’ve got a brush in front of me, I’m all right.”

Maud in her home studio.

Maudie is in cinemas today.