read an extract of "words to sing alive" – a celebration of Indigenous writers

This poem and essay, "TIDDA", is written by poet and editor Yasmin Smith.

"tingira tidda

wades at the timbers

in the mouth of an estuary

shaped like a moonbeam

gouged in the foot-pockets

of spongey shivered sapwood

bowed by wet bodies,

tidda’s body sings

how are we to see her

blossoming limbs to the

brackish currents,

her fingertips spun

by seagrass strings

tidda returns to

drowned river-valley,

tidda becomes nestled

in holy tendrils of algae

tidda sinks in cavities

to the mangroved-deep,

as moon jellies swarm

beneath the newly redeemed"

My grandmother’s language sits on the back of my tongue like pale honey. I haven’t quite learnt how to speak her words, yet I know someday I will swallow them sweet. So I choose a word, instead, that has swirled between the many generations of my sister-cousins and sissys and

aunties. A word we have always shared in comfort and community: tidda or tidda-girl. A word that weaves us tightly to the truth of who we belong to. Reminding me of who I am tied to by blood, by spirit, by bone. When I was a child, tidda would come with a string of laughter as my mother would playfully say: hey tidda, here tidda, where you going, tidda-girl? I never knew

the weight of this word until I watched her passing, surrounded by daughters, by sisters, by aunties.

Tidda holds joy and grief. Tidda holds all the women who I have never met or am yet to meet or will someday meet again: my great-grandmothers swimming from islet to island, my mother gathering stars above moonlit-sea, my grandmothers wading in saltwater creeks. I think of the universality of our languages that tow meaning into understanding, like the evening moon tugging the tide into early dawn. I think of the brief moment I walked by Thelma Plum on a sidewalk café in West End: hey sis, she says. I text my tiddas: you’ll never guess who I just saw on the street! Tidda captures our bonds of acknowledgement but it also welcomes the newness of connection. Too often tidda is unspoken because as language spins us together – relationally, spiritually, metaphorically – it does so by an unvoiced invitation of acceptance and the reciprocity of being received.

Tidda is in the exchange and in the gifting. I think of the tiddas I have read in stories, like May

in Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air. Of the time my mother and I wept in the dark at the cinema as we watched Molly and Daisy and Gracie, three tiddas return home across Country, trekking through sprawls of desert-flower in Rabbit-Proof Fence. I admire the tiddas who have handwoven our histories into baskets and bangles and dillybags. These strong lineages of

sisterhood – stroked into paintings – in the lapse of time and dance, in ceremony, in celebration.

When I listen to traditional language being sung or spoken or shared I am stirred by all of this sovereignty, embodied and owned, by First Nations creators. We ode ourselves to those around us, to the generations before and to those who may come. But in truth, this word makes me think of my closest. Of the sister who I have left, now that my mother has gone. Tidda, my sister, I cannot think of a better world to swim in if you were not here in sunlight and song.

Yasmin Smith is a poet and editor of South Sea Islander, Kabi Kabi, Northern Cheyenne and English heritage. Her poetry has featured in Meanjin, Overland, Australian Poetry Journal, Island, Best of Australian Poems, Griffith Review and more. Winner of the Gwen Harwood Poetry Prize in 2024, she has also been shortlisted for the Judith Wright Poetry Prize and longlisted for the Nakata Brophy Prize for Young Indigenous Writers. She is currently an editor at UQP, where she oversees the First Nations Classics series, and knits together her love of stories, art and pop culture.

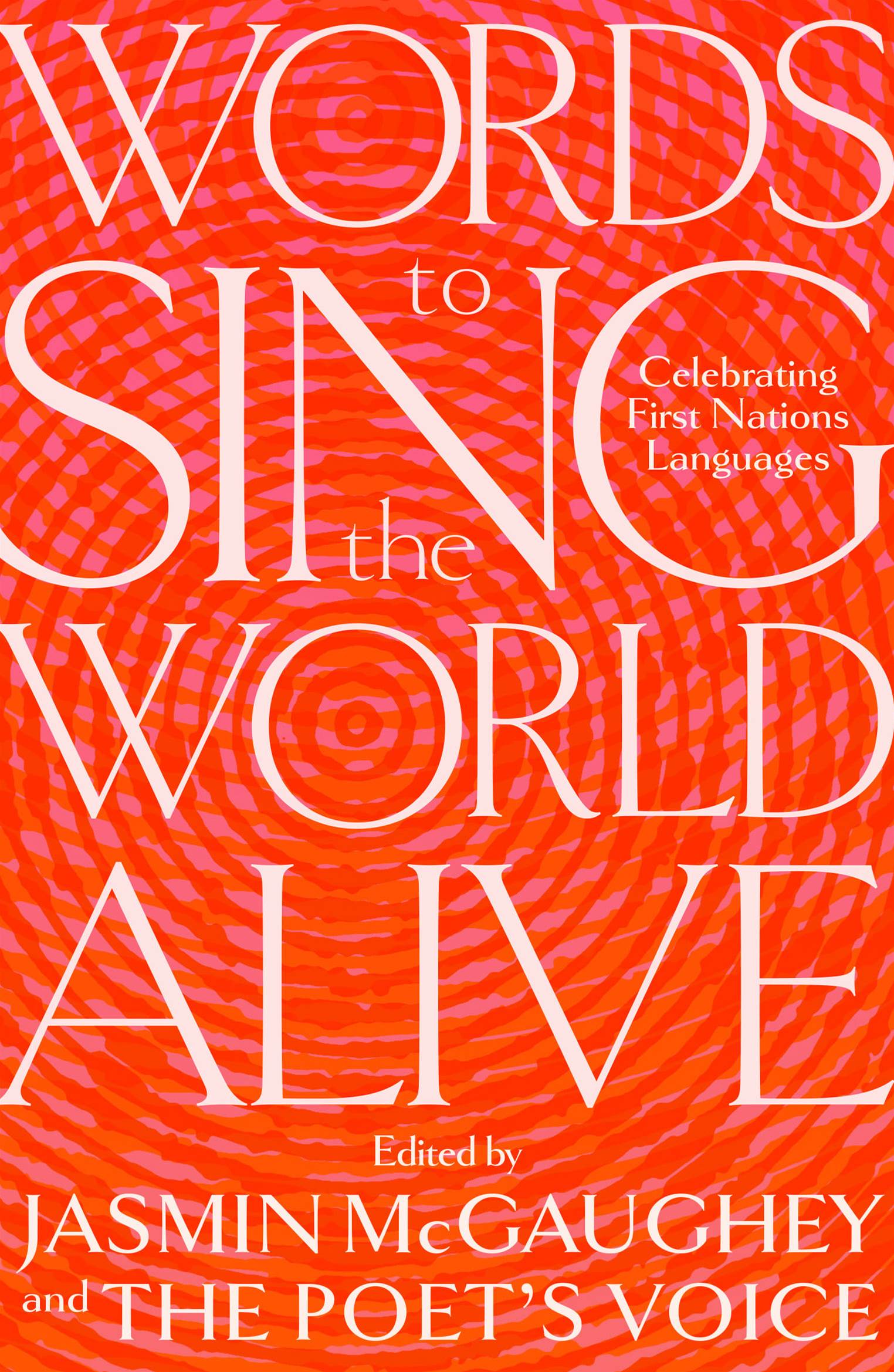

Essay excerpt TIDDA by Yasmin Smith in Words to Sing the World Alive edited by Jasmin McGaughey and The Poet’s Voice (UQP), $34.99, out 29 October.

_(9)_(1).png&q=80&w=1120&c=0&s=1)